Ventilation isn’t the magic bullet that’s going to solve the COVID-19 pandemic and instantly make any indoor space healthy and safe for its occupants. But it’s increasingly being talked about as an important factor in reducing the risk of transmission for schools and office spaces that are looking to reopen this fall, alongside more familiar safety protocols like masks, social distancing, and personal hygiene practices.

In last week’s installment of our ongoing series on ventilation, we took a look at the growing awareness of COVID-19 airborne transmission, as well as media coverage of ventilation and air purification in schools and commercial spaces. We also provided an overview of our own HVAC system, which includes an HRV ventilation unit, as an example of an existing system that goes above and beyond what’s currently installed in the average office space.

This week we’re diving into the specifics: Even if we have an advanced commercial HVAC system, how do we know if we’re meeting coronavirus guidelines about ventilation, filtration, and air purification? Using the Energy Circle office as a case study, we try to answer some important questions about the health and safety risks of returning to work.

What Are COVID-19 Ventilation Standards, and Are We Meeting Them?

COVID helped us realize that our state-of-the-art HVAC system has pretty much been in “set it and forget it” mode for most of its operating life. A Foobot monitor had been telling us our IAQ was mostly good, our energy bills are OK, and it feels like a quality environment—crisp and comfortable, even on the 5 dog days. But, as the attention on airborne transmission of the coronavirus has risen, we realized that we didn’t fully understand how our own office system was operating, and whether it was set at the right levels.

Four main questions came up that we set about trying to answer, and in the process we’ve ended up making a few changes to our system and set some goals for the future. Here’s what we learned.

Question #1: As more and more scientific and medical research suggests that indoor transmission is the primary source of COVID spread, what can we do to circulate more fresh air through our office—to make it more, well, like the outside—so airborne viruses will not stick around in our breathing air? What are the recommended rates of air exchange and ventilation in a commercial building like ours, and is the Energy Circle office currently meeting those levels?

Unfortunately, while the CDC has released COVID-19 guidance on office ventilation and filtration, they aren’t very specific on the subject of ventilation, and their recommendations for commercial buildings essentially boil down to:

-

Increase ventilation rates

-

Reduce or eliminate air recirculation

-

Keep systems running longer (24/7 if possible)

-

Consult ASHRAE

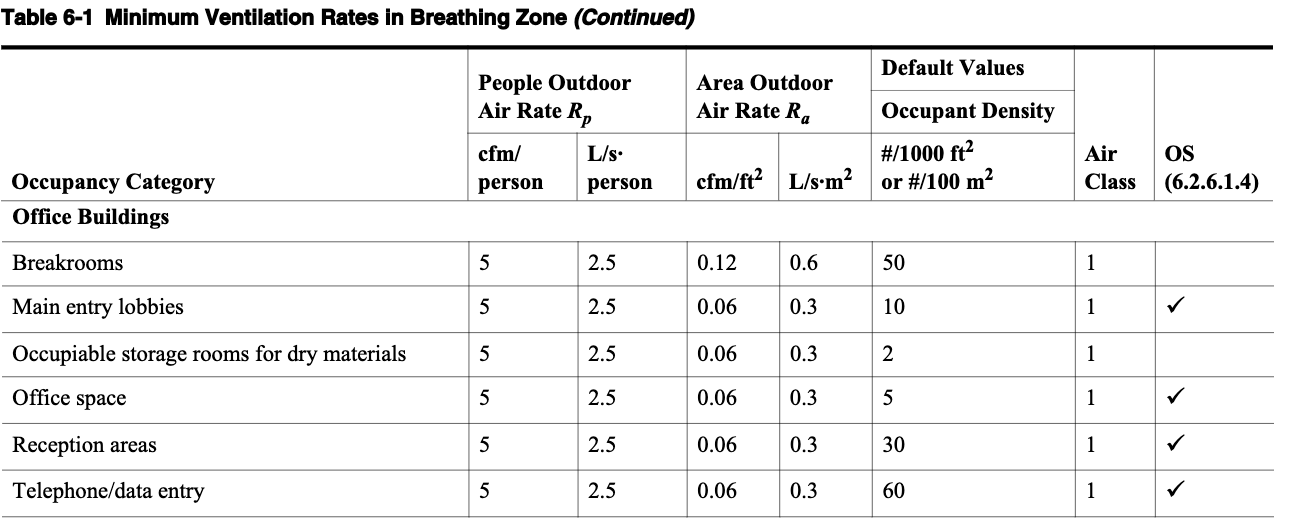

Neither the CDC or ASHRAE (which published its own Guidance for Building Operations During the COVID-19 Pandemic in May 2020) specifies what the recommended ventilation rates should be increased to, but we can at least take ASHRAE’s existing standards as a starting point. ASHRAE 62.1 and 62.2, which cover ventilation and acceptable indoor air quality in commercial and residential buildings, were updated in November 2019, and provide the following guidelines for office buildings:

From ASHRAE 62.1, Table 6-1: Minimum Ventilation Rates in Breathing Zone, we can see that the minimum ventilation rate throughout office buildings is 5 CFM/person.

From ASHRAE 62.1, Table 6-1: Minimum Ventilation Rates in Breathing Zone, we can see that the minimum ventilation rate throughout office buildings is 5 CFM/person.

If we go by ASHRAE, we want our system to be operating at a minimum air flow rate of 5 CFM (cubic feet per minute) for every person in the office. Between the two floors of our building that our fresh air system services, there were rarely more than 40 occupants at any given time in early 2020, prior to the pandemic. That means that we would only need an air flow rate of 200 CFM, and if you remember from the screenshot of our HRV dashboard in last week’s blog, our system had been set up to run at more than 400 CFM, or more than twice ASHRAE’s minimum rate.

ACH, or Air Changes Per Hour

One of the things that bugged us, however, is that CFM/person isn’t a particularly accessible metric—unless you’re hanging around with a bunch of HVAC geeks. Recent media coverage around ventilation rates, for example (like this great piece in the New York Times exploring the ventilation system of a city subway car), simplify discussion around ventilation into an easier-to-understand figure: how many times per hour indoor air is replaced with fresh outdoor air, known in the HVAC world as ACH, or air changes per hour.

Calculating the ACH in the Energy Circle office requires knowing the rate of air flow exchange. Before making any COVID adjustments, the system was set at 400 cubic feet per minute, or 24,000 cubic feet per hour, and the total volume of our office space is a little over 100,000 cubic feet. (It is important to note that these settings were established based on full occupancy and we’re only at about 1/10 that number now with most folks working remotely.) Here’s how our math works out:

ACH = CFM x 60/volume of office space

400 (Our CFM target for Ventacity HRV) x 60 min/hr = 24,000

8,618 (square footage totals of office space, added up from spreadsheet) x 12 foot high ceilings = 103,416 ft cubed (total volume of office space)

24,000/103,416 = .23 ACH

An ACH of 0.23 means that the air in our office building is being completely replaced once every four hours (this is only the air change rate from our ventilation system, of course—our office building is far from airtight and we’re certainly getting some as-yet-unmeasured natural ventilation from air leaks). Yet according to the Harvard School of Public Health’s Healthy Buildings Program, classrooms should be aiming for 5 ACH. That’s a massive gap—nearly 22x our ventilation rate!

Granted, most offices generally won’t need as much ventilation as a school building, but ASHRAE recommends a minimum of 7.5 to 10 CFM/person for most educational facilities, which is only 1.5 to 2x that of office buildings. Several building scientists and indoor air quality experts confirmed our math, and said that our ACH of 0.23 was generally in the ballpark for adequate ventilation in a home or office setting. So how could a sophisticated system like ours, producing excellent indoor air quality metrics (which we’ll get into in more detail below), be so far off from an authoritative recommendation about necessary air changes for health?

While we know we are well exceeding ASHRAE’s CFM/person recommendations, there was a general sense of confusion among the experts we spoke to as to what the right increase in ventilation rates might be when dealing with a global pandemic (this is what happens when building science meets medical science), whether such high ACH levels were even achievable for many offices or classrooms, and if ACH is the correct metric we should be using to talk about ventilation (for one, it doesn’t take room occupancy into account).

What we are doing, at the recommendation of our friends Keith O’Hara of Eco Performance Builders, Dan Perunko of Balance Point Home Performance and Paul Raymer of Heyoka Solutions is increasing our HRV’s air flow rate above 500 CFM to reach an even 0.3 ACH. We’re also changing the weekly settings so our ventilation system runs more often: two hours before, and two hours after occupancy—for an additional “flush” the office air. We’ve set it up to run for several hours on the weekend as well.

Question #2: Air filtration and purification is being widely discussed as one of the primary tools most businesses and schools have to fight against airborne COVID-19 transmission. Does Energy Circle have adequate filtration in our office?

Filtration

Compared to ventilation, the CDC’s guidance on office filtration is pretty specific and straightforward:

“Improve central air filtration to the MERV-13 or the highest compatible with the filter rack, and seal edges of the filter to limit bypass.”

Outside of federal or industry guidelines, MERV 13 filters are one of the solutions that media outlets seem to be picking up on the most—even CNN just released an article about the need for retail stores and supermarkets to upgrade their filtration systems to MERV 13. Back in July, McKinsey & Company published an article asking if HVAC systems could help prevent transmission of COVID-19, which includes some nice infographics illustrating the efficiency of MERV and HEPA rated filters.

So, did Energy Circle have MERV 13 rated filters in our office already? Yes and no, as it turns out. There are MERV 13 filters at the fresh air intake of our HRV unit, but the exhaust filters in our office ductwork (where any contaminants that might come into the space would be trapped) were only MERV 8. We’re upgrading (though we’re finding resistance from the HVAC company that maintains our system, who says installing a MERV 13 filter would add too much “wear and tear”).

Air Purification

The CDC doesn’t list any recommendations for air purification. ASHRAE’s guidelines are nearly identical to the CDC’s, but they do ask you to “consider” installing ultraviolet light air purifiers and portable air cleaners with HEPA filters, two points missing from the CDC’s website.

UVC lights are installed inside ductwork, but how effective they are at eliminating airborne viruses traveling through your duct system is up for debate—as Allison Bailes points out over at his Energy Vanguard blog, air moves so quickly through ductwork that you’d need UV lamps with a significant amount of power to effectively “kill” germs, bacteria, viruses, and other air pollutants.

A good portable air purifying device that continuously circulates air through a HEPA filter (which captures 99.97% of particles with a size of 0.3 microns) seems to us like a better choice. We used a useful calculator created by the Harvard School of Public Health to determine the specs of the air purifier we’d need (measured in CADR, or clean air delivery rate), based on the size of the main room in our office. We’ll be adding three portable units, and once we have them set up, our total air changes will be the combination of CFM from our HRV and the CADR from our portable air purifier (ventilation rates are additive in this way), so boosting our overall air changes with filtration seems smart. (Note: the legitimacy of filtered air being additive to ventilation air seems to be yet another point of contention within the building science community.)

3) How do we gauge whether any of this is actually producing more healthy air in the Energy Circle office? How can we keep closer track of indoor air quality levels, so we know our HVAC system is delivering the results we’re looking for?

We’ve recently installed an Awair Omni in the office, a commercial grade device with high quality sensors, and RESET certification. A single Omni device won’t provide an accurate measure for our entire office space—we’d likely need 3 or 4 to cover everywhere—but it has a number of advantages: It’s small, can sit right on a desk or a table, and has dedicated sensors that can pick up on a number of IAQ readings, including:

-

Humidity

-

Temperature

-

CO2

-

TVOCs

-

PM2.5

-

Light

-

Noise

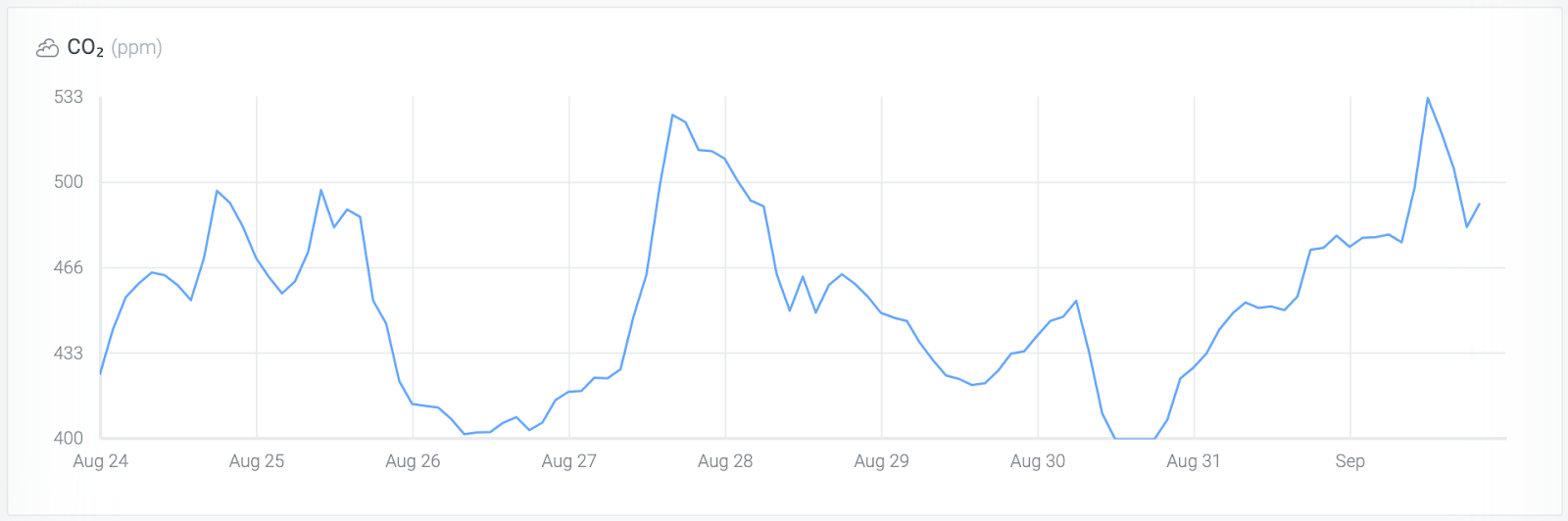

The Omni has been logging data since mid August, and so far we’re within RESET’s high performance standards for commercial interiors on CO2, VOCs, and PM2.5.

A look at the recent CO2 levels in our office, as recorded by our new Awair Omni IAQ monitor, showing the inconsistency of people working at the office, and that we’re within “High Performance” standards, according to RESET.

A look at the recent CO2 levels in our office, as recorded by our new Awair Omni IAQ monitor, showing the inconsistency of people working at the office, and that we’re within “High Performance” standards, according to RESET.

Our Omni won’t tell us if there are airborne coronaviruses in our office, but we can keep an eye on the levels of other air pollutants to get a better understanding of how effectively our ventilation, filtration, and air purification systems are working. Since the primary source of CO2 in an office is from human respiration, higher levels of CO2 could indicate that, regardless of our CFM/person settings, our ventilation system isn’t changing the air in our office quickly enough. Anything below 1000 ppm is considered “Acceptable” by RESET standards for CO2, and below 600 ppm is “High Performance.”

We can also watch relative humidity levels, as a recent study suggests that low humidity creates conditions favorable to the coronavirus, allowing it to remain airborne longer and spread farther in a room.

IAQ devices need to collect data over a longer period of time to be useful in drawing any kind of accurate conclusions, so while over the first couple of weeks of data collection things are looking good, we’ll be checking back in with our findings later this year.

Note: As we mentioned earlier, we have had a consumer grade Foobot in the office for awhile, but as Joe Medosch explained on a recent webinar comparing IAQ devices, there are better, more reliable options available today (also, our Foobot is old enough that a firmware updating error is preventing us from even accessing our old data).

4) Is there an energy penalty for our ventilation efforts and if so, what?

It’s important to mention that enhanced ventilation and indoor air quality measures do come at a financial cost. The extra air we’re gaining all needs to be heated or cooled, so there’s an energy penalty that we’ll need to watch. Fortunately, the Ventacity HRV is best-in-class in the commercial category, with up to 93% recovery efficiency. This will diminish as air flow increases (we’ve been operating above 80% efficiency at 400 CFM) but in COVID times, we’ve decided to err on the side of ventilation over energy efficiency.

We’ve decided that the additional costs are worth it if it even incrementally improves the chances of employees remaining healthy. Viruses aside, there are inherent benefits when people don’t call out sick, and studies have shown that high air pollutant levels in an office can affect cognitive functions.

The Next Steps in Ventilation Awareness

Even for a company like Energy Circle, it’s been confusing trying to make sense of federal and industry guidelines on ventilation and indoor air quality, and we know that most other businesses and schools will be forced to work with less. We’re following the recommendations of professionals we know and respect, our Awair tells us we have mostly spectacular IAQ, and yet there’s a wide gulf between our own ventilation rates and what we see being recommended for schools. If our best in class system can’t even get close, what’s it mean for the reality of most schools that have antiquated or non-existent ventilation systems?

Education is rapidly evolving around airborne coronavirus transmission, but we believe that there is a growing awareness (as indicated by rising media coverage) around the importance of ventilation—one that could continue to grow this fall as more people around the country move indoors, and companies and schools are pressed to open their doors again and return to “normal.” We should all be working to reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19 as much as possible, and our HVAC systems may have an important role to play in that fight.

For those of us working in or adjacent to the home performance and HVAC industries, we need to take the lead in setting the conversation on ventilation—not as medical experts but as building scientists who understand how HVAC systems can and can’t be utilized for public health and safety. This is an opportunity to both provide an important service in a unique time of need and to introduce more commercial customers and homeowners to the idea of healthy homes and indoor air quality—concepts that are undoubtedly important at this very moment, but are also likely to outlast the coronavirus pandemic.

[Look out soon for Part #4 of our series on ventilation.]